The problem as I saw it was one of scale and scope. To fully prepare the cabinet would take far more time than I currently had available.

I had to scale down to address any of this work with integrity. It is easy enough to go over the work in a theoretical overview, for that ultimately is only words.

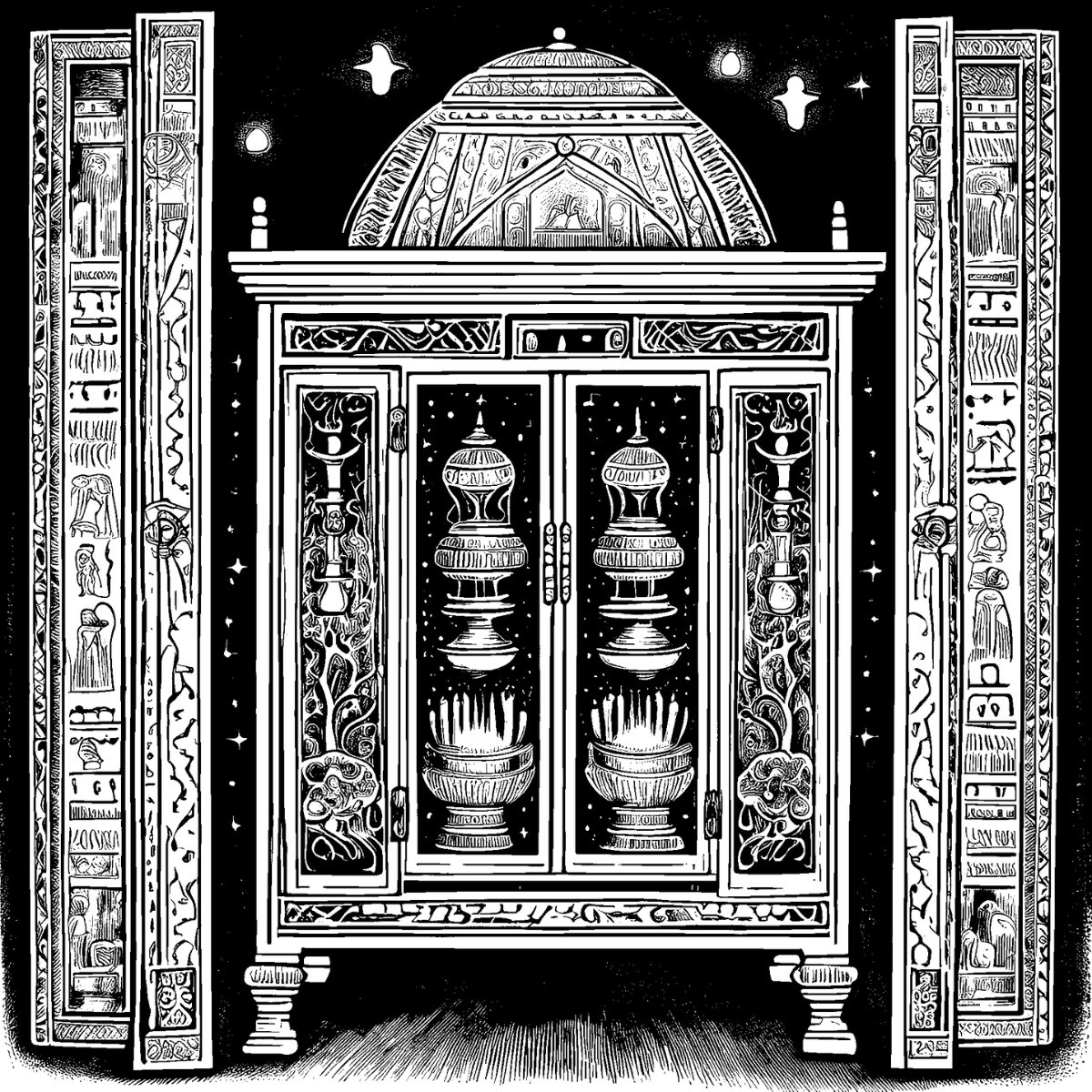

But to effectively create the actual wunderkabinett would require my life’s blood, along with total dedication at the exclusion of all else. Or so they told me in the mountain academy.

I wondered if it was actually true that this was the only true way. I recalled the story of Lahiri Mahasaya, one of the first known householder-yogis, who was an example to all that the achievement of the yogic life could also be attained in everyday normal circumstances.

Well, I thought, if it hasn’t been done yet, it will be now. That can be my contribution to this effort. I will, by my example, fulfill the obligations of a keeper of a wunderkabinett while still living an absolutely average life. No disruption on the home front, no extreme seclusion, arduous practices or spooky experimentation, or very little. The goal instead, like the search for the grail, is to be able to recognize the kabinett and its contents as they appear through the clues in the day to day manifestation. Following the clues, tuning the perception toward the realm where the clues point naturally opens to the experience.

Artifacts from these experiences become hardened and solidified as ritual or magical objective symbols. These, when gathered, become the contents of the cabinet.

There is no reason to fill the cabinet with stuff that belonged to others, unless it was given to me for that purpose. There is no reason to place objects in it that I think could be, or someday will become, significant. The task is clear – only do as I must, and allow intuition free rein to discover what and where, as well as how and why.

Averroes, the Sufi scholar of Cordoba, sits with me, as he has since I first read name when I was still in high school. It was as if his name shone with golden light, in letters written in the air. That night I wrote my first inspired piece, describing the aftermath of his death as his body became sand that filtered down through the bed, through the floorboards and finally into the earth below. That was how he appeared to me – by allowing me to describe his disappearance.

His small portrait, painted Arab-style, is in an elaborate Spanish frame. At the bottom of it is his name in calligraphic script, Englishified. He looks out at me through this image. By his name, just above it, in an oval insert at the base of his portrait, is an image of the scholarly city where he worked and taught. I can walk those streets with him, invisibly, for it is a city of the past, and as a woman I would not have had free passage in his day. He introduces me to Avicenna, who is his colleague, and to others who are his pupils and companions. I weep with joy at this meeting, for they are all extraordinary beings. I discover that to them I am not invisible.

“We exist in different times and we meet when there is a call.”